Securing the Peace Guarantees a Total Win

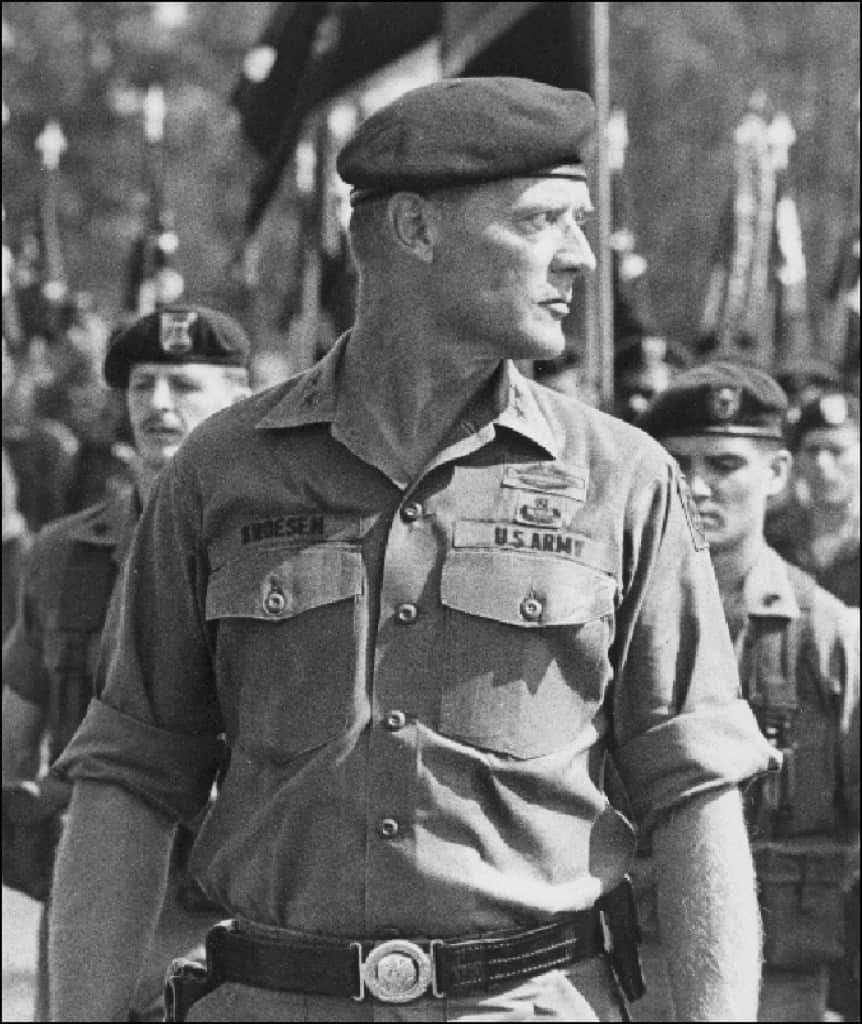

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, U.S. Army retired

One of the most important contributions of the U.S. Army in the conduct of international affairs has been the respect and reputation developed by the units and soldiers that have been deployed around the world in the past century. There has been no doubt about the combat capabilities of the forces that have demonstrated their dominance whenever they have been committed. But there should also be no doubt that those serving in peacetime deployments, particularly when families have accompanied the troops, have been almost equally responsible for long-term impact.

Convincing Testimony

I have many times maintained that World War II was won only after long years of occupation of Germany and Japan, years in which our military government detachments brought about the change of governments of those nations. Their steadfast alliance with us through now at least three generations is convincing testimony that we did it the right way.

It was Gen. George C. Marshall, learning from our occupation of the Rhineland in Germany after World War I, who initiated the teaching and training of those detachments, even before Pearl Harbor and along with the earliest steps toward building the Total Army we would need to win on the battlefield. Marshall never received the public approbation accorded the World War II battlefield commanders, but his understanding and management for solving the strategic requirements of that war, almost singly arrived at, were a vital contribution to the final success.

From the beginning, that success required the defeat of the enemy armed forces, but success was finalized only by our military government detachments and by the soldiers and families who changed the occupation from a conquering Army to conditions of friendly partnerships. From the earliest days, the children of those countries came to know our soldiers as generous, compassionate members of their communities. Their parents in those destroyed and destitute countries were soon to follow. The numbers of German-American and Japanese American marriages that resulted testify to the development of trust and friendship. In succeeding years, the number of Vietnamese-American families and the cordial and enthusiastic welcome experienced by our war veterans who have returned to Vietnam as tourists is further testimony that our soldiers have a positive impact.

It was not always easy or acceptable to the suffering populations as we confiscated buildings and private homes without compensation to the owners and renters who were displaced and had to be accommodated by their neighbors or some local community organization, but in time we built our own living quarters and other facilities and helped restore the normal functioning of the populations. Throughout those years, personal relationships developed and a popular recognition of the security aspects of our presence grew. Over time, the tolerance of the German and Japanese people for maintaining facilities for foreign armies, for the annual exercises and the damages inflicted on their roads, bridges and buildings by less-than-careful military units, was quite remarkable, but it was a tolerance fostered and cultivated by the soldiers and families of the occupying forces.

Not Without Fault

This is not to claim that all was without fault or misunderstanding or disagreements. The words My Lai and Abu Ghraib establish that we have made some serious mistakes, fully deserving of harsh criticism. Our stockade populations testify that our soldiers included the normal complement of bad actors who required police and disciplinary activities, but we also suffered an occasional attack on our personnel and facilities.

There are also examples of failures to achieve normality that should have been sought, usually because we presumed a short military campaign would be followed by a quick return to normality. The most glaring such failure might be the invasion of Iraq when the capture of Baghdad was to be sufficient for our purpose. For the first time in our history, we went to war without an increase in the structure of our forces. When asked what size Army would be needed, our chief of staff estimated 300,000. He was derided, ignored and banned from further discussions of strategic needs, but the years following that campaign do not prove any success in what our intent might have been. There were no military-government detachments to deploy, no forces to occupy the critical locations and inadequate means to create and sustain a friendly, cooperating government.

The Army today is contemplating a future in which technology will provide the means for a smaller force to conduct military campaigns. Pre-eminent in that quest is the use of robots that can reconnoiter fire weapons, provide security alarms, deliver supplies and more. But they cannot replace the humans needed to occupy critical objectives, control the population and cultivate a culture and cooperating government that can secure a peace. Our post-hostility ambassadors must be included in the force needed for a total win.

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret., served as vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army and commander in chief of the U.S. Army Europe. He is senior fellow of the Association of the U.S. Army’s Institute of Land Warfare.

This article originally appeared in ARMY magazine, April 2018, VOL. 68, NO 4. Reprinted by permission.