If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and family. You can also help the American Security Council Foundation shape American policy.

Written by Alan W. Dowd, ASCF Senior Fellow

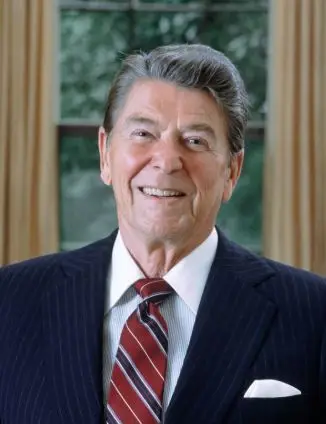

Our August issue discussed what is arguably the most important pillar of President Ronald Reagan’s peace-through-strength policy: military strength. However, military strength alone is not enough to keep the peace. In this issue, we look at the other three pillars of peace through strength.

Engaging the World: 2nd Pillar

Reagan was utterly opposed to building a Fortress America and withdrawing from the world. He recognized that engagement is an essential element of peace through strength—and the best way to address problems overseas before they explode into unmanageable crises.

“We in America have learned bitter lessons from two world wars,” Reagan explained during a visit to Normandy. “It is better to be here, ready to protect the peace, than to take blind shelter across the sea, rushing to respond only after freedom is lost. We’ve learned that isolationism never was and never will be an acceptable response to tyrannical governments with an expansionist intent.”

Yet growing numbers of Americans have forgotten the hard-learned lessons of Normandy and Pearl Harbor, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, Munich and Nanking.

Although the word choice may be a bit different, the Obama administration’s “nation building at home” mantra and the Trump administration’s “America first” doctrine are two paths to the same destination: an America disengaged from, and disinterested in, the world.

It’s a paradox, but for America, an inward-looking foreign policy defined purely by self-interest has the effect of undermining America’s interests. Reagan understood this and cautioned against retreating from the world.

“Our national interests are inextricably tied to the security and development of our friends and allies,” Reagan observed. “The ultimate importance to the United States of our security and development assistance programs cannot be exaggerated.”

That explains why spending on international development and humanitarian assistance jumped 50 percent during Reagan’s first term.

Reagan knew that a policy of engagement secures America’s interests and promotes America’s ideals.

For instance, the Marshall Plan prevented Western Europe from sliding into the prison yard of communism, transformed Europe from an incubator of world wars into a partnership of peace and prosperity, and created a massive market for U.S. goods.

The Berlin Airlift not only rescued a city from starvation and tyranny, but also dealt a blow to Stalin.

Closer to our time, PEPFAR, USAID and PMI have saved tens of millions of innocent lives, while promoting stability in key regions. Vin Gupta, an officer in the Air Force Medical Corps, and Vanessa Kerry of the Harvard Medical School have found that these and other humanitarian-assistance programs are not just acts of generosity. They serve U.S. interests: “Countries that received the highest levels of per-capita health aid enjoyed near-immediate results in terms of improved state-stability metrics.” Such development aid “not only saves lives but also appears to facilitate the rise of more peaceful societies.”

More peaceful societies are more stable—and both peace and stability are in America’s interests. Indeed, humanitarian-assistance programs “can serve both strategic and humanitarian purposes,” Gupta and Kerry conclude.

Reagan would agree and would argue that a foreign policy characterized by zero-sum transactions and pennywise cuts has the effect of undermining America’s interests.

Supporting Democratic Partners

A third pillar of Reagan’s peace-through-strength strategy is supporting democratic partners and movements.

Reagan argued that “support for freedom fighters is self-defense” and “is tied to our own security.” Thus, he provided material support—technological assistance, weapons, covert deployments, shows of force, direct military intervention on occasion—to anti-communist forces and democratic movements resisting aggression in Central America, the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, Africa and Central Asia.

Yet Reagan recognized that the arsenal of democracy isn’t limited to bullets and bombs. He had at his disposal, like all presidents, the bully pulpit. And he used it to great effect to support democracy and promote peace.

Arguing that “a little less détente…and more encouragement to the dissenters might be worth a lot of armored divisions,” Reagan openly encouraged the oppressed and condemned their oppressors.

“The United States is a democratic nation,” Reagan said in the coldest days of Cold War I. “Here, the people rule. We build no walls to keep them in, nor organize any system of police to keep them mute…It’s difficult for us to understand the restrictions of dictatorships, which seek to control each institution and every facet of people’s lives.” These inherent differences between the free world and dictatorships “put us into natural conflict and competition with one another.”

He backed up his words with resources. Recognizing that democracy “needs cultivating”—and that democratic movements can weaken our autocratic enemies from within—Reagan declared, “It is time that we committed ourselves as a nation, in both the public and private sectors, to assisting democratic development.”

Toward that end, Reagan helped create the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) “to foster the infrastructure of democracy—the system of a free press, unions, political parties, universities—which allows a people to choose their own way, to develop their own culture, to reconcile their differences through peaceful means.”

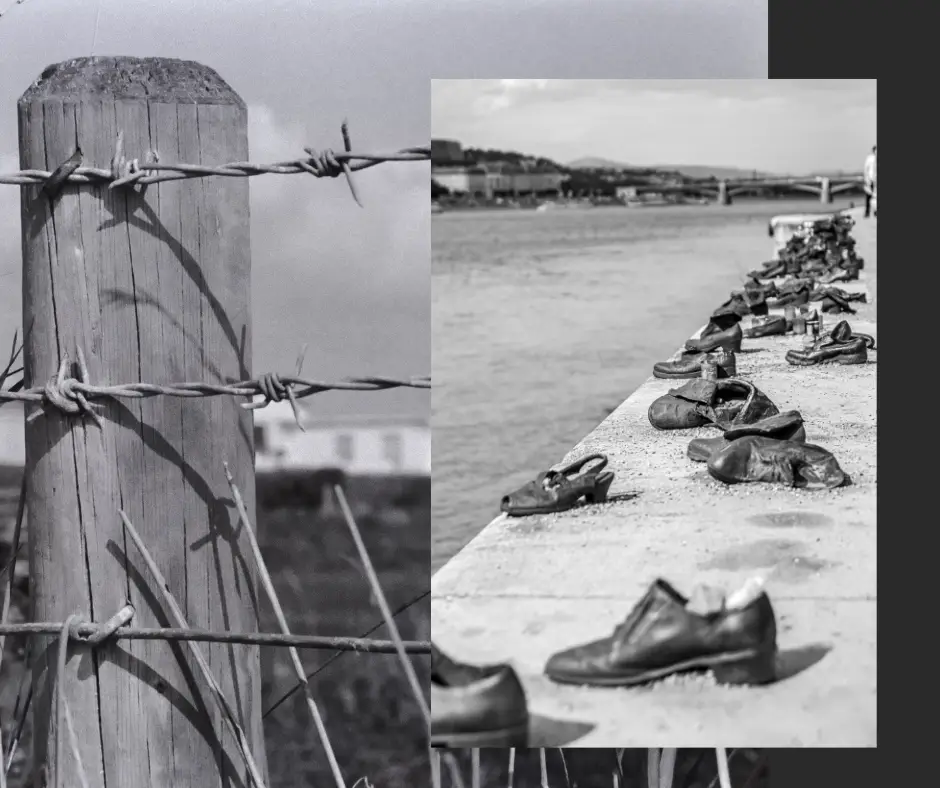

Under Reagan, NED provided aid—directly and indirectly—to pro-democracy movements in communist Poland, communist Czechoslovakia, communist Hungary, communist Nicaragua, and even to pro-democracy groups inside the Soviet Union.

Reagan also empowered the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe to promote free government, to “carry the truth to captive people,” and to speak with “the conviction that by carrying the American message abroad we strengthen the foundation of peace.”

In short, rather than undermining, cutting or zeroing out initiatives promoting free government, Reagan bolstered them. “If the rest of this century is to witness the gradual growth of freedom and democratic ideals,” he said, “we must take actions to assist the campaign for democracy.”

It’s no coincidence that the democratic tide surged during Reagan’s presidency.

Cultivating Alliances

A fourth pillar of Reagan’s peace-through-strength strategy is cultivating alliances.

“It’s not just strength or courage that we need, but understanding and a measure of wisdom as well. We must understand enough about our world to see the value of our alliances,” Reagan explained. “We must be wise enough about ourselves to listen to our allies, to work with them, to build and strengthen the bonds between us…Our goal is peace. We can gain that peace by strengthening our alliances.”

Reagan was an unwavering NATO supporter. He never called NATO obsolete, never browbeat NATO laggards, never threatened to withdraw from NATO, never raised doubts about America’s commitment to NATO.

Instead of viewing NATO and other alliances as a liability to be managed, Reagan recognized our alliances as a precious resource to be nurtured—and an essential part to America’s strength and security. Indeed, he emphasized the parallels between his peace-through-strength doctrine and what he called “NATO’s strategy for peace,” which was and is premised on the idea that NATO must “be strong enough…to stop aggression before it happens.”

Instead of worrying NATO allies, Reagan reassured them by echoing the words of the North Atlantic Treaty: “If our fellow democracies are not secure,” he said, “we cannot be secure. If you are threatened, we’re threatened. If you’re not at peace, we cannot be at peace. An attack on you is an attack on us.”

Reagan grasped NATO’s enduring role and relevance. As post-Soviet Europe began to hemorrhage, Reagan reminded a new generation of leaders, “There is an antidote to chaos…Its name is NATO.” And Reagan endorsed NATO’s growth as way to enhance America’s security: “Room must be made in NATO for the democracies of Central and Eastern Europe,” he declared.

Beyond Europe, Reagan called the U.S.-Australia bond “an alliance of trust” and “shared values.” Of Japan, he said, “Together, there is nothing Japan and America cannot do.” He described South Korea as “a staunch ally” that, along with Japan, is “building a better tomorrow.” He praised the Philippines as “a longtime ally” and “a remarkable people…joined together with faith in the same principles on which America was founded.”

If he were alive today, Reagan would applaud our British, French, Italian, Spanish, German, and Canadian allies at work in the Indo-Pacific deterring our common foe. He would emphasize that French and British aircraft joined U.S. forces shielding Israel from Iran’s missiles and drones. He would cheer NATO allies contributing to operations protecting international shipping from Houthi attacks. He would salute Poland for spending 5 percent of GDP on defense, Japan and Sweden for doubling defense spending, Germany for getting serious about defense. He would thank South Korea and Australia for helping Ukraine. He would call on Washington to support Ukraine without equivocation and to send defensive arms to Taiwan without hesitation.

And he would remind policymakers that peace through strength requires more than military strength.