If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and family. You can also help the American Security Council Foundation shape American policy.

Written by Alan W. Dowd, ASCF Senior Fellow

February 2026—Noting that the world has endured 19 consecutive years of decline in free government, Freedom House reports that 40 percent of the world’s population lives in “not free” countries, while just 20 percent lives in “free countries.”

By contributing to increased risks and costs for the United States and its allies, this retreat from freedom threatens U.S. interests. The United States thrives in a world where free governments and free markets flourish. The United States is more secure in a world characterized by more freedom. And the United States is less secure when freedom is in retreat. Free peoples, after all, don’t threaten American citizens, territory or interests; don’t take up arms against one another; don’t waste lives and treasure waging war against one another; and don’t undermine the liberties of one another. Tyrants do those things. As President Franklin Roosevelt observed when the future seemed to belong to tyrant regimes, “No realistic American can expect from a dictator’s peace international generosity, or return of true independence, or world disarmament, or freedom of expression, or freedom of religion, or even good business.”

That explains why Roosevelt (along with Winston Churchill) sought to build a postwar order more conducive to free government, free trade and free exchange—and in doing so, to tip the global balance of power away from tyranny.

“Circumstances during the first half of the 20th century had provided physical strength and political authority to dictatorships,” as historian John Lewis Gaddis explains. “Why should the second half have been different?” The answer: “a striking shift in the attitude of the United States” from focusing inward to “planning a postwar world in which democracy and capitalism would be secure.”

This effort was bipartisan and enduring: Roosevelt declared, “Freedom of person and security of property anywhere in the world depend upon the security of the rights and obligations of liberty and justice everywhere in the world.” President Ronald Reagan added, “We must take actions to assist the campaign for democracy.”

With the United States and its Free World allies promoting an international order premised on free government and free exchange, as historian Robert Kagan observed more than a decade ago, “The balance of power in the world has favored democratic governments.” The alternative, Kagan warned, is a world where great-power autocracies undermine liberal democracy, where the liberal-democratic order is replaced by disorder, where there are “fewer democratic transitions and more autocrats hanging on to power.”

And here we are. Echoing the Freedom House findings, a 2025 study by the University of Gothenburg in Sweden reports that “The world has fewer democracies than autocracies for the first time in over 20 years,” that “liberal democracies have become the least common regime type in the world,” and that “nearly three out of four persons in the world—72 percent—now live in autocracies…the highest since 1978.”

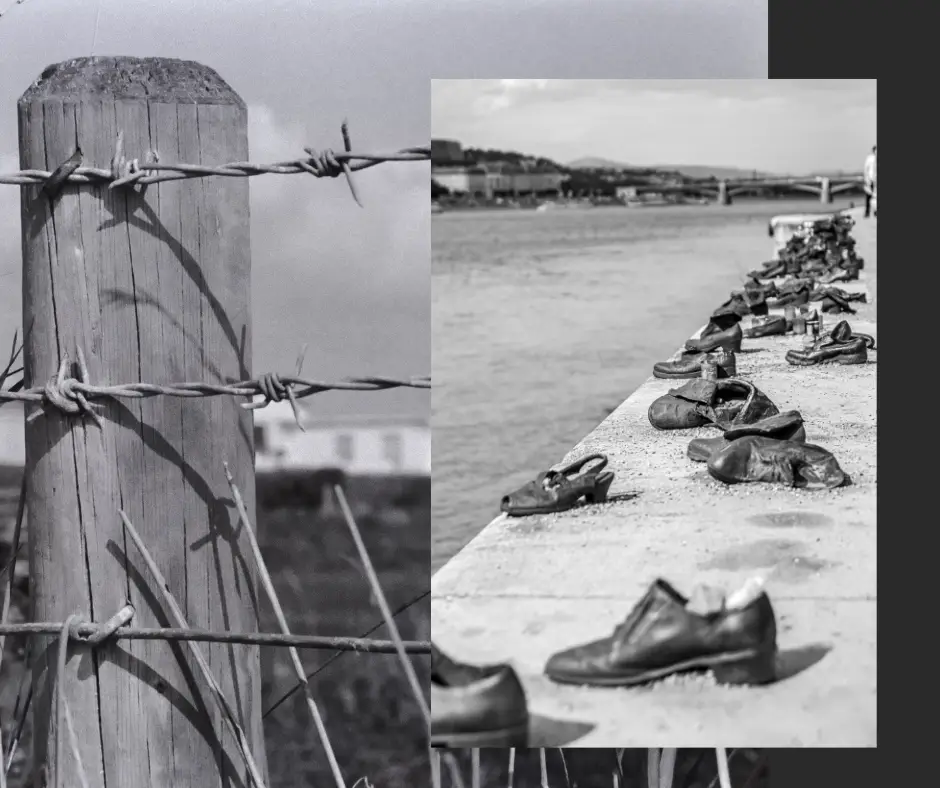

The bad news doesn’t end there. Regrettably, the Free World is struggling not only against external challenges posed by tyrants, but also against internal challenges.

First, a growing segment of the Free World seems apathetic about freedom and oblivious to what history teaches about freedom’s enemies. For a time, Soviet communism’s collapse served as proof not just of the superiority of free government and free exchange, but of the futility of government by coercion and economics by top-down control. Yet among many of those who have come of age since the end of the Cold War, there’s neither an innate recognition that free exchange is better than the alternative nor a default belief in the power of individual liberty. 49 percent of American adults born since 1981 (the Millennial Generation and Generation Z) would “prefer living in a socialist country,” 51 percent of Millennials reject capitalism, and, most stunning of all, 18 percent of Generation Z and 13 percent of Millennials have positive views of communism.

Second, Freedom House warns that “democracies are being harmed from within by illiberal forces” aiming “to corrupt and shatter” the very institutions that keep the Free World, well, free. Recent public-opinion research, for instance, finds that “a wide range of the American people, of all political stripes, seek leaders who are fundamentally anti-democratic.”

The key to arresting these trends is to help our neighbors recognize that the rule of law, free government and free exchange deliver better outcomes than rule by control, conformity and coercion.

Reagan made this case powerfully and repeatedly.

“Freedom is a fragile thing, and it’s never more than one generation away from extinction,” he warned. “It is not ours by way of inheritance; it must be fought for and defended constantly by each generation.”

“Individual liberty is dependent on the rule of law,” he explained. We must promote and pursue “the ultimate in individual freedom consistent with law and order.”

Reagan called the right to private property an “essential” element of individual freedom.

“We cannot have prosperity and successful development without economic freedom; nor can we preserve our personal and political freedoms without economic freedom,” he noted. “Government,” he added, “can’t interfere with economic freedom without restricting the political and personal freedom of individual Americans.”

Looking beyond America’s borders, Reagan explained that “Development depends upon economic freedom…The developing countries now growing the fastest in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are the very ones providing more economic freedom for their people—freedom to choose, to own property, to work at a job of their choice and to invest in a dream for the future.”

Reagan’s insights about the interaction and interdependence of the rule of law, economic freedom, and political freedom are as important today as they were during the Cold War—perhaps more important given some of the generational trendlines noted above. The good news is that several indices, rankings and datasets—including measures comparing levels of political freedom, economic freedom, individual liberty, property rights, happiness, per capita GDP, life expectancy, environmental quality, government corruption, commitment to the rule of law, women’s empowerment and children’s wellbeing—serve as rocket-fuel for Reagan’s timeless insights.

Our next issue will dig into what those rankings and comparisons reveal about the power of freedom—and the danger of taking freedom for granted.