If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and family. You can also help the American Security Council Foundation shape American policy.

Written by Alan W. Dowd, ASCF Senior Fellow

JANUARY 2026—U.S., E.U., British, and Ukrainian officials have carved out a path to ending Putin’s war on Ukraine and securing a durable peace. Make no mistake: The compromise peace plan now ping-ponging around Europe and across the Atlantic is less than perfect. But as they have in the past, America and its allies can make such an imperfect peace work.

Minefields

First things first: There are minefields standing in the way of peace.

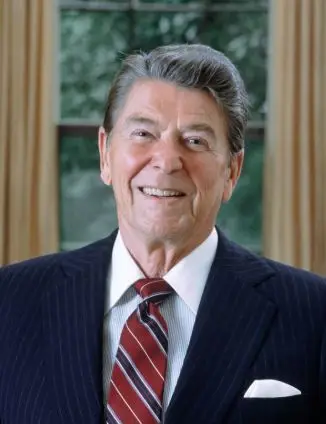

Chief among those minefields is Putin, whose idea of a negotiated peace is Ukrainian capitulation. Even if Putin agrees to a ceasefire, even if he signs a peace deal, the Free World will need to keep a close eye on his actions. Putin’s record is one of deception and destruction, treachery and treaty violations. An updated version of President Ronald Reagan’s “trust but verify” maxim will be in order: “distrust and scrutinize.” Distrust everything Putin says, scrutinize everything he does.

Another possible minefield: the Ukrainian people. As a dictator, Putin can sign a treaty and order his subjects to observe it. As a democratically elected leader, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine can do only the former. Ukraine’s people could reject any number of unpalatable elements of the peace plan—the ceding of territory, the creation of DMZs on Ukrainian territory, the vagueness of postwar security commitments.

Congress could become an obstacle. In hopes of keeping America engaged after the guns fall silent, Zelensky wants the peace plan “voted on and supported by the U.S. Congress.” This is understandable in theory; congressional buy-in would cement U.S. commitment to postwar Ukraine, but it may prove problematic in practice. Congress is increasingly inward-looking. Consider the difficulty of passing Ukraine military aid last year, which took months and revealed a deeply fractured House.

Commitments

If the peacemakers can navigate those landmines, peace is possible.

It’s important to recognize that a durable Ukraine-Russia armistice “is a core interest of the United States” because it would “stabilize European economies, prevent unintended escalation or expansion of the war,” and “enable the post-hostilities reconstruction of Ukraine” and “its survival as a viable state.”

Those words come from President Donald Trump’s 2025 National Security Strategy. Put another way, even one of Ukraine’s toughest critics recognizes that postwar Ukraine must be sovereign—and strong enough to remain sovereign. That means clear lines must be drawn for Russia and clear commitments must be made to Ukraine.

Let’s start with the commitments side of the ledger.

A document outlining the peace plan reports that the U.S. and Europe will “work together to provide robust security guarantees,” including “legally binding” commitments “to restore peace and security in the case of a future armed attack” against Ukraine. “These measures may include armed force.”

This isn’t the equivalent of NATO’s Article V mutual-defense clause. But it’s a step in the right direction. The guarantees—a thick thatch of 28 bilateral security agreements with Europe, America and other partners—will promote defense and industrial cooperation, harden postwar Ukraine, and deter a third Russian invasion.

That brings us to the lines that must be drawn for Putin. The most tangible of those lines will be represented by a peacekeeping mission spearheaded by Multinational Force Ukraine (MNF-U). Although MNF-U will not technically be a NATO mission, NATO will play a key role: After all, most of the troop-contributing nations will be NATO members; NATO has an entire command focused on security assistance for Ukraine; and NATO’s military commander (USAF Gen. Alexus Grynkewich) has been notably present at ceasefire talks, which is a good sign.

According to the aforementioned peace-plan document, MNF-U will be “operating inside Ukraine” and will “assist in the regeneration of Ukraine’s forces…securing Ukraine’s skies [and]…supporting safer seas.”

That reference to “safer seas” is critical. Ukraine’s long-term health depends on the free flow of goods through the Black Sea, which means MNF-U must have a robust maritime component. For MNF-U partners concerned about international law, Articles 11, 14, 51, 52 and 55 of the UN Charter would check that box.

Another critical element of MNF-U: Though European-led, it will be “supported by the U.S.,” including through a “ceasefire monitoring and verification mechanism…to provide early warning of any future attack.” Reading between the lines, that suggests America’s unique intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance assets will be used in “securing Ukraine’s skies” by keeping a constant watch over Russian threats.

Since the possibility of postwar peacekeeping was first floated, Europeans have emphasized that they would need the U.S. to provide “backstop” capabilities. While Trump has opposed deploying U.S. ground troops and stressed that “European nations are going to take a lot of the burden,” he concedes, “We’re going to help them.” Toward that end, he ordered Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Dan Caine to work with allied militaries on ways to support the peacekeeping force, with the U.S. likely to provide specialized airpower, intelligence, and other enabling capabilities.

Importantly, Europe’s MNF-U plan—and America’s contributions to it—don’t commit American troops to fight Putin’s armies in the mud of eastern Ukraine. They arguably do the opposite: the better equipped, better situationally aware, and better connected to the rest of Europe Ukraine is, the more likely that peace takes root and the less likely that American troops will have to engage Putin’s military.

In short, this effort is in the national interest.

Support

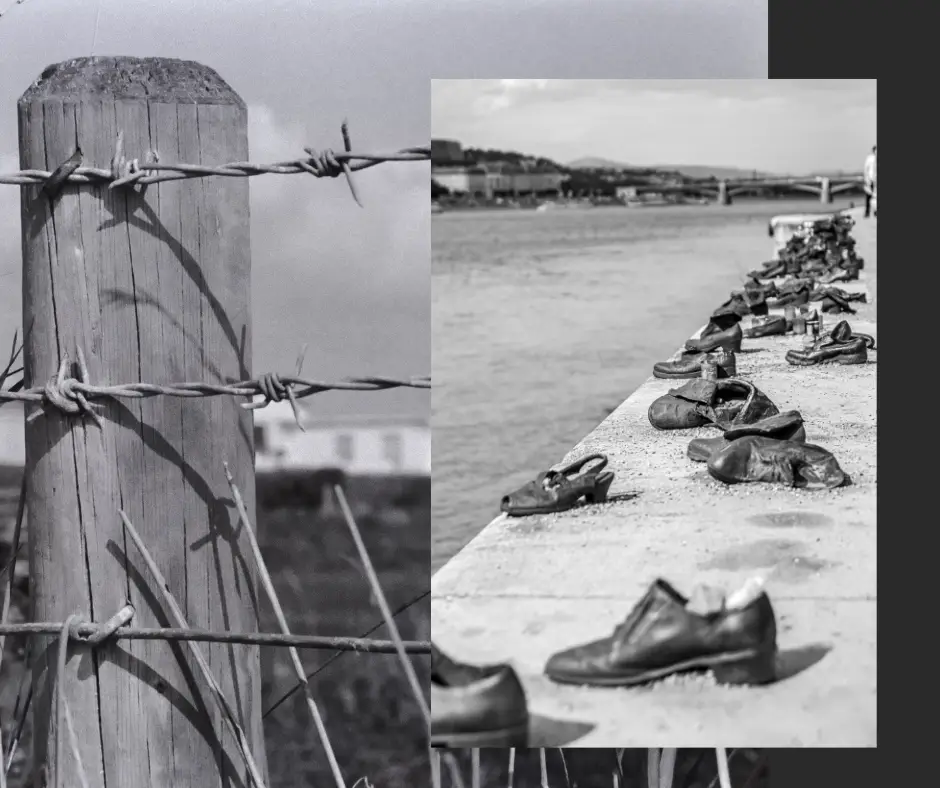

Reconstruction—estimated to approach $1 trillion—will be key in fending off another Russian invasion. A modern-day Marshall Plan—led by the E.U., with support from America, Britain, Canada, Turkey, Australia, Japan and others—can help rebuild what Putin’s war of war crimes has destroyed. These donor nations would underwrite some of the costs of reconstruction, but frozen Russian assets also should be part of the equation.

Another important ingredient in postwar Ukraine’s success and stability is what has been revealed in wartime Ukraine. To Putin’s surprise, his war has proven that Ukraine is a developed, democratic, cohesive nation-state, which means postwar Ukraine won’t be like postwar Bosnia, Libya, Iraq or Afghanistan—places that were broken not because of foreign intervention, but rather were so broken that they invited foreign intervention. MNF-U personnel will be able to focus on rebuilding Ukraine’s defenses, keeping the peace and monitoring the border. And MNF-U will have a dependable partner in the Ukrainian military.

Ukraine’s membership in the E.U. will further fuel Ukraine’s postwar stability. European leaders in December said they “strongly support” Ukraine joining the E.U. While it’s not the equivalent of NATO’s Article V, E.U. membership ensures that if a member is attacked, other E.U. members have an “obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power.” In short, E.U. membership comes with benefits beyond trade—benefits that will strengthen Ukraine’s postwar security.

Even so, postwar Ukraine’s security posture will be unique among European nations. After all, the vast majority of European nations derive their security from NATO membership. Ukraine won’t be joining NATO any time soon, if ever. As a result, Ukraine won’t be able to count on the NATO cavalry. So, Ukraine will become a fortress—bristling with defenses and always bracing for the next war. If Ukraine wants a glimpse of its future, it should look to Israel. It’s a grim existence. But it’s preferable to the alternative.

The good news is that postwar Ukraine won’t be as isolated as the Israel of 1967 or 1973. As detailed above, postwar Ukraine will have close security ties with neighboring democracies—and fortified overland supply lines with those democracies.

History

Some say this postwar plan is too difficult or too dangerous due to Russia’s occupation of Ukraine’s land and Russia’s intentions. But history reminds us that neither lingering territorial disputes nor simmering hostilities are dealbreakers when it comes to providing security to partners in the crosshairs—and that occupied territory isn’t necessarily lost territory.

Consider the Soviet-occupied Baltics. Washington made clear in 1940 it wouldn’t recognize Stalin’s absorption of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—and maintained that stance until they regained their independence in 1991.

Consider post-World War II Germany. Despite serious territorial disagreements and massive armies in close proximity to one another, West Germany was rearmed and invited into NATO. The U.S. didn’t formally recognize the post-World War II territorial-political settlement in Germany or across Europe until 1975. And the German people didn’t abandon their hopes for reunification, which weren’t realized until 1990.

Consider post-World War II Japan. The Red Army seized Japanese islands at the end of the war. To this day, Tokyo does not recognize Russian control over those islands. Despite this territorial disagreement, America guaranteed Japan’s security in 1951 and entered into a mutual-defense treaty in 1960. That treaty is still in force.

Consider the Korean Peninsula. Despite territorial disagreements, despite the absence of a peace treaty, despite the massive hostile army north of the 38th Parallel, America provided security guarantees to South Korea in late 1953. Those guarantees are still in force. And South Koreans still look forward to reunification.

In none of these examples did America or its partners legitimize the permanent ceding of territory. Rather, they recognized the present difficulty of liberating occupied territory. And they envisioned the future prospect of the reunification of lost lands.

These examples remind us that a less-than-perfect peace can work—but only if America is engaged and committed to making it work.