If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and family. You can also help the American Security Council Foundation shape American policy.

Written by Alan W. Dowd, ASCF Senior Fellow

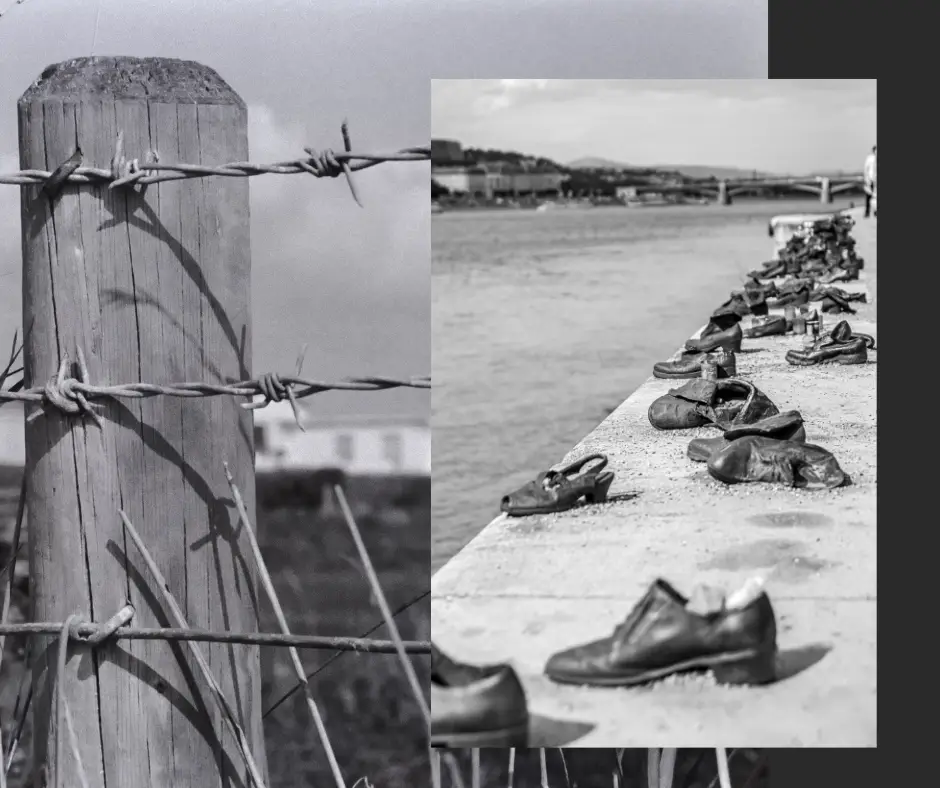

October 2025- Moscow has launched attack-drones into Poland (a NATO member); warned Poland that its eastern territories were “a gift from Stalin”; moved nuclear weapons into Belarus; aided and funded attacks against U.S. forces; violated the CFE Treaty and INF Treaty; provided targeting data to support Houthi attacks against allied ships; interfered in elections throughout NATO’s membership roster; and dismembered NATO aspirants Ukraine and Georgia. Russia is also diverting 35 percent of its government spending into its military; conducting a campaign of sabotage operations across NATO’s footprint; firing off intermediate-range missiles; and sharing weapons with Iran and North Korea.

Add it all up, and it’s easy to see why French President Emmanuel Macron calls Putin “a predator…at our doorstep”—and why NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte warns that “Danger is moving towards us at full speed.”

The operative words here: “our” and “us.”

Putin’s Russia is a threat to our security—the security of all 32 members of the NATO alliance, including the United States—and to all of us who are fortunate enough to live under the NATO umbrella, from NATO’s eastern flank (which borders Russia) to NATO’s western flank (which is just 2.5 miles from Russia).

To deter Putin from launching yet another war of aggression, NATO needs America—and America needs NATO.

For Europe

America is not merely important to NATO; it is essential. It pays to recall that after World War II, as the Red Army menaced Europe’s western half, Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg tried to provide for their own security by forging a mutual-defense pact known as the Brussels Treaty. Prime Minister Paul-Henry Spaak of Belgium said aloud what his allies quietly understood: Any alliance that didn’t include the U.S. would be “without practical value.”

Stalin would agree. Before NATO was created, Stalin trampled upon the Yalta agreement and Poland’s independence, supported communist forces in the Greek Civil War, pressured Turkey for basing rights, toppled Czechoslovakia’s democratic government, and blockaded West Berlin. The blockade finally got the attention of U.S. policymakers. In April 1949, the United States joined Britain, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Portugal in signing the North Atlantic Treaty.

The heart of the treaty is Article V, which declares, “an armed attack against one or more…shall be considered an attack against them all.”

That got Stalin’s attention.

Indeed, America’s role in NATO is not merely that of first among equals; it is foundational. The Article V security guarantee, backed by the United States and embodied in the NATO alliance, made clear to Moscow that America would defend every member of NATO and every inch of NATO territory. Without that guarantee, there’s no security in Europe, as history has a way of reminding those on the outside looking in, from Cold War Hungary to post-Cold War Ukraine.

Ever since NATO’s founding, the presence of American troops on European soil has sent an unmistakable message to Moscow: Crossing this line means you are going to war against the United States—no ambiguity, no question marks, no doubts about the consequences. That message has been reinforced by America’s nuclear arsenal, some of which is deployed on European soil, underscoring for Moscow that an attack on America’s European allies would ultimately threaten Russia’s very existence.

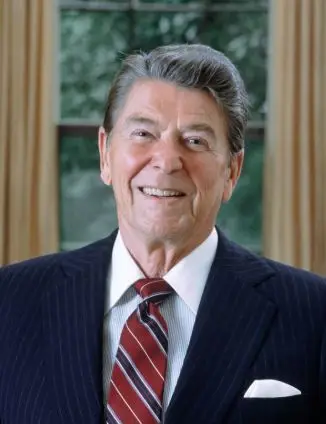

Sometimes that message has been delivered wordlessly, through tests, exercises, and deployments. Sometimes it has been delivered directly, as when President Dwight Eisenhower responded to Khrushchev’s boasts about the Red Army’s conventional advantage in Germany: “If you attack us in Germany,” Eisenhower bluntly explained, “there will be nothing conventional about our response.”

That certainty of response—the promise that the costs of aggression will be far greater than any potential benefits—is the essence of deterrence. And it has worked in Europe since the end of World War II, thanks to the United States’ security guarantee.

This has allowed Europe’s NATO members to steadily transform the continent from a zone of constant conflict into an exponent of peace and prosperity. Indeed, America’s presence in Europe, anchored and shaped by NATO, provided the stability Europe needed to build a community. In other words, it was NATO that laid the groundwork for the economic cooperation that has knitted the continent together; it was NATO that built trust between longtime enemies France and Germany; it was NATO that smothered German aggressiveness—something everyone from Margaret Thatcher to Mikhail Gorbachev welcomed.

Following the Cold War, the promise of NATO membership helped resolve territorial disputes throughout Eastern Europe, thereby further stabilizing the continent. In fact, NATO called on countries aspiring to join the alliance to resolve those disputes before being considered for membership.

A Grateful Continent

As Spaak and his neighbors realized before NATO’s founding, none of this would have happened had the United States not remained engaged in Europe after World War II—and, for that matter, after the Cold War. NATO is what kept America engaged. Europe’s leaders are grateful for that—and have been for decades.

In the early hours of the Cold War, West Germany’s Konrad Adenauer thanked U.S. policymakers “for the helpful hand that was extended to us-to the German nation—by the Americans” and praised America for the Berlin Airlift, when “America recognized her duty to be the leader of free nations.”

“America has been the principal architect of peace in Europe,” Thatcher explained as the Cold War began to thaw. “The debt the free peoples of Europe owe to this nation—generous with its bounty, willing to share its strength, seeking to protect the weak—is incalculable.”

Just days after the Berlin Wall fell, Lech Walesa of Poland declared, “The people in Poland link the name of the United States with freedom and democracy, with generosity and high-mindedness.”

One of Walesa’s more recent successors, Andrzej Duda, argues that “Poland and Europe need more America, militarily, politically and economically.”

“Only the U.S. can deter Putin from attacking again,” Britain’s Keir Starmer concludes.

“We cannot replace American support,” Italy’s Giorgia Meloni adds.

“The world can’t be secure without America,” Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky bluntly explains. “Without strong U.S. security commitments, everything else is weak.”

Finland’s Sanna Marin agrees: “We would be in trouble without the United States.”

Marin and Zelensky, Starmer and Meloni and Duda, Adenauer and Thatcher and Walesa are, of course, right. The United States does much to help Europe, mainly through the transatlantic bond represented by NATO. Our next issue will explore how much Europe—and NATO—does to help the United States.